Designing the story for Control:Override : Schrödinger’s protagonist on a budget

Some time ago, I released Control:Override, my first commercial game on Steam and itch.io. Rather predictably, it has not done well financially. But I did learn several things along the way.

In this post, I will talk specifically about the story.

A barebones overview of the story:

You play as a hacker who has hacked into the rogue AI that he created. His goal is to terminate the AI. There is also a multi-ending story to uncover through optional files should the player wish to do so.

I’d give a warning about spoilers here but based on the game’s sales, it is very unlikely that anyone reading this was going to buy or even know about the game to begin with. However, as I am not discussing the actual details of the story that much here, most of it won’t make much sense unless you’ve played the game.

In my very biased opinion, I think the game’s story is worth the 2 or so hours it takes to complete. So I recommend doing so before proceeding any further.

You can play the game here on steam and itch.io.

Anyways, there is a lot to talk about here.

How do you “design” a story? Aren’t you supposed to write a story?

Yes, I wrote the entirety of the script(with someone else as the editor). I’m by no means a good writer. I thought more about the structure of the story than the content. And I designed the structure first based on the game’s requirements. The story was shaped by the structure and requirements of the rest of the game. I will elaborate on this “design” aspect later on.

Where did I start with the story?

To be honest, I didn’t start with a story in mind for this game. The original premise of the jam version was that you are a virus overriding the world inside a computer as you please.It was something I came up on a whim to explain some of the mechanics. It didn’t even have to be sci-fi. For example, witchway has a very similar mechanic that lets you control platforms, but that’s in a fantasy setting.

The sci-fi setting was entirely a coincidence. However, thinking back. It was the right decision. The sci-fi elements were a good excuse to talk about AI from the perspective of a programmer. And it honestly came really easily to me. That and I like sci-fi.

Takeaway: Play to your strengths when writing the story. Think about what sort of life experiences you have and how you can integrate them into your story. Make something you will enjoy.

The story requirements:

When I started expanding the game from the jam version, I wanted to have a proper story in the game. These were my requirements:

- The story would interfere as little as possible with the puzzle elements: Some puzzle games use puzzles to express parts of their story. However, the movement mechanics already made puzzle design restricting. I did not think that it would be possible to design a level that expressed a story element while keeping the puzzle interesting. As a result, I decided to tell the story through unlockable story fragments to completely separate it from the gameplay.

- The story must be doable with my limited artistic abilities: I don’t have the talent for beautiful artstyle or cinematographic cutscenes. I don’t have the budget to hire actual artists. The presentation requirements of the story must be doable with my stickman level art. Due to this I resorted to a text-heavy story told through text-logs because text is cheap to implement unless you want VA.

- The story should not require any boss fights: The c game’s mechanics did not lend well to boss fights. Moreover, the game’s design was reliant on a rewind mechanic that had become a big part of the game’s puzzle design. And rewinding would honestly ruin the thrill of boss fights. So I decided that if the game has an antagonist, s/he should not actually want to fight the player so that I have an excuse to not put boss battles in-game.

- The story should build up and reach a satisfying conclusion by the end of the game: Again, this was to give the player a reason to continue solving puzzles. This was also the reason for adding mystery elements to the story.

- The story and the characters should have a lasting impact on the player: As an indie developer, I don’t expect my game to reach that many people. I expect even fewer to actually bother with the story. However, I want the few people who do so to be positively affected by the game.

- The player should not have to bother with the story if he does not want to: I figured that no matter how much effort I put into the story, some people will still mash through the dialogue and only play for the puzzles. So, I made the meat of the story optional.

Settling on the characters and themes:

The first change I made was to replace the virus with a human hacker as the playable character. The reason was that it was much easier to write a character arc for a human rather than a computer program.

Then came the antagonist. Portal had already set the standard here with GLADOS which plenty of games copied. I didn’t want to do that. Moreover, there was also the requirement to avoid boss fights.

This meant the antagonist, at their core, should not want to fight the player. I started by envisioning an antithesis of GLADOS. That is, an AI that appeared untrustworthy and illogical/insane at first glance but gradually seems more and more sane. This became the basis for MIR-AI, the narrative core and the most beloved character in the game(if the 10 responses in the post-game surveys are any indicator).

I thought that it’d be more interesting if the protagonist himself had created the AI. The act of destroying your own creation naturally creates narrative tension. To double down on this theme, I added another character as the co-creator(if the protagonist is the “father”, this’d be the ‘‘mother” ) of the AI. The parenthood theme was rather cliche but I think the game manages to do enough with it to warrant its inclusion.

There is a fourth character in the game. He’s mainly there to spit cheesy lines and act as a foil to the “mother” character. He does his job well. Sometimes, a simple character just works.

That’s it, the game has just 4 characters. There are a few unimportant named ones but these 4 are the ones who actively play a role in the story. Having so few characters actually helped keep the story scope small and manageable by myself.

Takeaway: If you don’t have time/budget for it, keep the scope of your story small. Also, ensure that all of those characters are utilized in the story and in the themes.

Designing the story:

My next task was to outline the flow of the story. Since piecing together the story was an important part of the game, I wanted to integrate it as a story element. It seemed logical for a hacker to uncover secret files so I decided to tell the story through those.

The player would play through a set of puzzles, unlocking some secret files along the way. After a set was completed, there would be a cutscene that would have some relevance to the content of the secret files(different dialogue based on whether or not you read them). This’d repeat a few times until the final cutscene culminating in one of the endings.

I also wanted to factor in possible Player behavior(i.e not reading any file at all, skipping important files etc). To incorporate that into the narrative, I decided to make it in-character for the protagonist to do both. In other words, he must have a reason to read as well as to not read the files. So, I came up with a backstory for the protagonist where he has some past trauma that he doesn’t want to be reminded of by reading those files. This guilt ended up being the core of the protagonist’s character.

The main character is not a blank slate. He has a name. A backstory. With a detailed backstory comes the problem of delivering that exposition to the player. At the same time, I don’t think the story-skipping players would want to hear all of that. So I came up with the following:

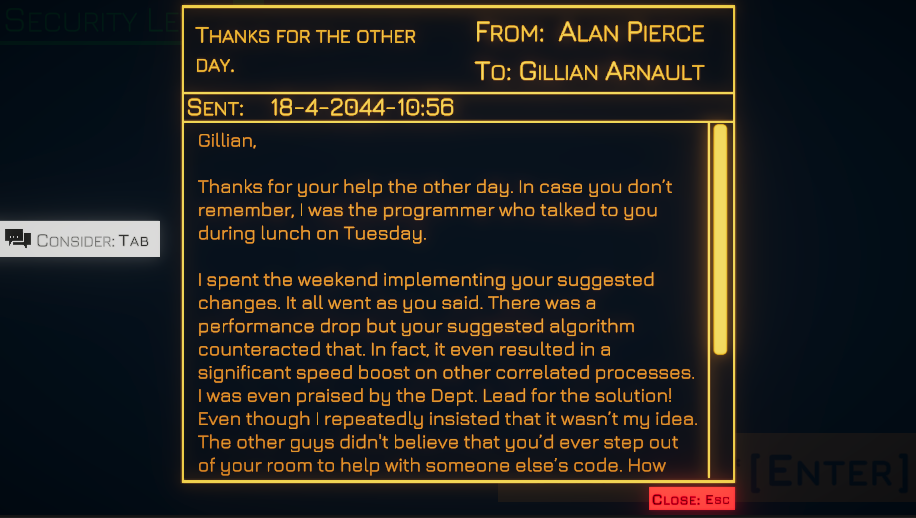

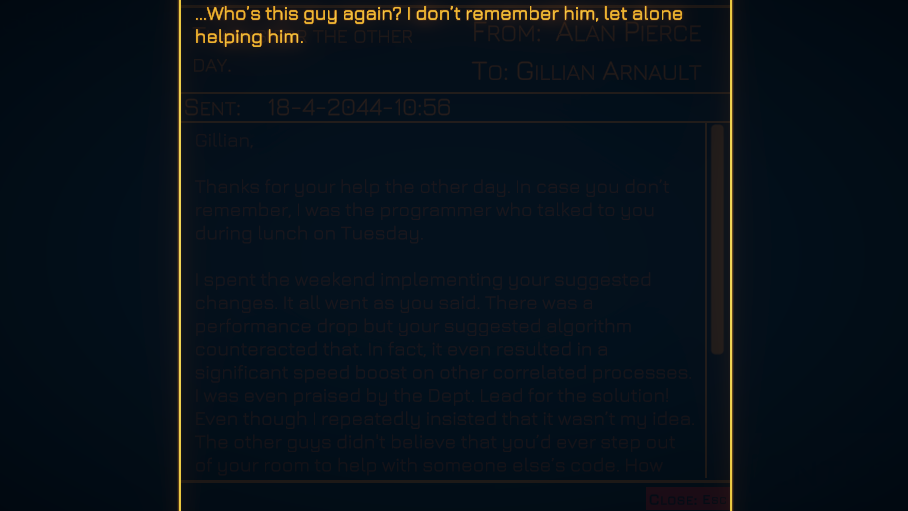

The “Consider” mechanic:

How do you make text logs interesting? In the case of Control:Override, I put text logs inside my text logs and had them complement/contradict each other.

If the player opens a file, they can choose to hear an optional monologue by the main character that will explain his perspective of the events. If the unlockable files are this game’s equivalent of loot dropped from defeated enemies(completed levels), then the monologue is the item description. Flavor text.

But it’s not just that. The main character is biased. He starts off distrusting the AI. He has his own interpretation of other characters that are not necessarily accurate.

He’s also rather rude.

His biases color his monologues and through them, the player’s interpretation of the events.

He’s also rather rude.

His biases color his monologues and through them, the player’s interpretation of the events.

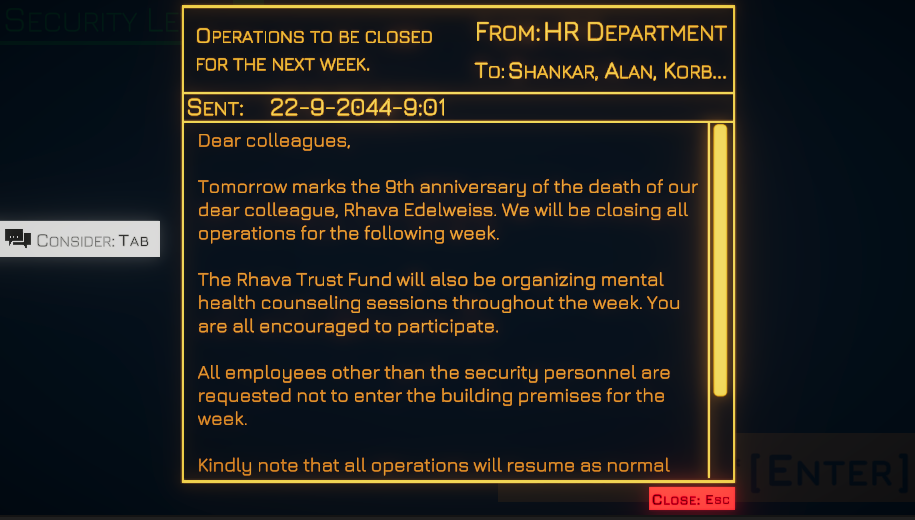

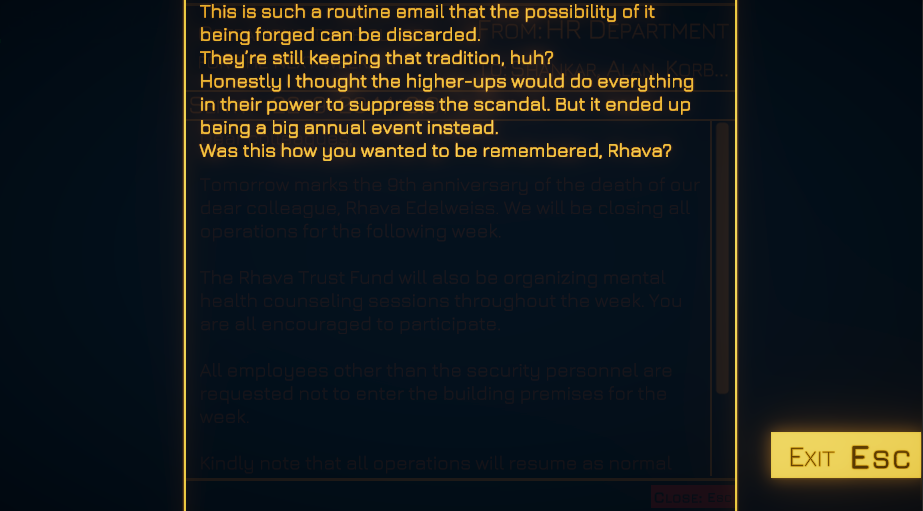

This is a simple email about a corporate BS holiday. But to the player character, it is a source of conflict and guilt.

This is a simple email about a corporate BS holiday. But to the player character, it is a source of conflict and guilt.

We can see that in the “Consider” monologue.

We can see that in the “Consider” monologue.

By having the “Consider” monologues contradict/complement the actual text logs, I could provide additional information and lenses into the player character.

The player and the main character start at level 1 with the same goal: Solve puzzles and stop the AI. The MC reads every file alongside the player. And he thinks about them. The player may not choose to hear them but it’s still happening in the background. And since it’s optional, the frantic story skippers don’t need to read my walls of text.

Both the player and the MC change as they read through the files. The player gets a deeper understanding of the story and the MC goes through character development. His monologues change. Should the player revisit old data logs, the player character will say different things about the same bits of information. His perspective has changed.

The player and the MC go through parallel but not identical journeys.

They might not like the MC but at the end of the story they will understand him and the weight/reasoning of each of the end-game choices.

It’s also possible that the player will not read any of the files. This type of player is represented by the thrill seeking hacker. You might say that this type of player is explicitly treating the game as a simple puzzle game by only caring about the puzzles. I address that too in the “bad” ending that this type of player will get.

Takeaway: Ensure that the player character and the players share the same goal. Integrate player behavior into the player character if possible.

But it is still plausible that he would read those files. Curiosity is human nature and doubly so for inquisitive hackers. As another reason, I gave him a subconscious reason to do so by making said traumatic event essentially a murder mystery that he never felt truly resolved. The protagonist also has a grudge against the AI due to past events.

Moreover, in genres where the challenge of gameplay(solving puzzles for puzzle games) can be the primary motivation of the player, you can certainly expect some of them to skip the story for the puzzles. This corresponds to the type of hacker that hacks for the sheer thrill/challenge of it.

Something Something Schrödinger:

As you can see, the protagonist has multiple reasons for his behavior throughout the game. And it’s all indeterminate until the player explicitly makes it clear through his actions. This is what I meant by the term “Schrödinger’s protagonist”.

If the player character’s nature is like Schrödinger’s cat, what is the equivalent of opening the box here?

That’d be making a choice. Choices are not always explicit. The simple act of choosing to solve a puzzle over looking at incriminating evidence says something both about the player and the player character. For the player, it means that they enjoy the puzzle-solving aspect more. For the player character, it means he’d rather drown in the thrill of solving problems than come to terms with the truth.

Looking at single files/text logs is also making a choice. In most cases, a rather trivial one. The first time the player does it is probably to just see what it does. It is the same for the player character. When they choose to look at more files, it is because their interest is piqued and they possibly want to know more. The more the player character looks at the more he questions and thinks. The lid of the box lifts bit by bit and the indeterminate player character converges into something concrete.

But the player is not aware of the implicit choices they are making. That is why I made the important choices explicit.

Plot relevant monologues are unskippable and tied to major plot development beats that the player MUST know to understand the story. They also act as a visible trigger to let the player know that something has indeed changed in the game.

Takeaway: The verbs in your game(kill, read, loot, solve) can also be choices.

Takeaway: important events where the story branches should be obvious to the player.

Limiting the branching story for the sake of my sanity:

The player can read the files in any order and the game should also acknowledge that. However, I could not just account for every possibility. Moreover, the game’s story ended up written in such a way that a sequence of files(basically a diary for a character) ended up as the singular trigger for the ending. It was not worth accounting for every variation in reading order for them since I’d also need to show the MC’s mental state through the monologues.

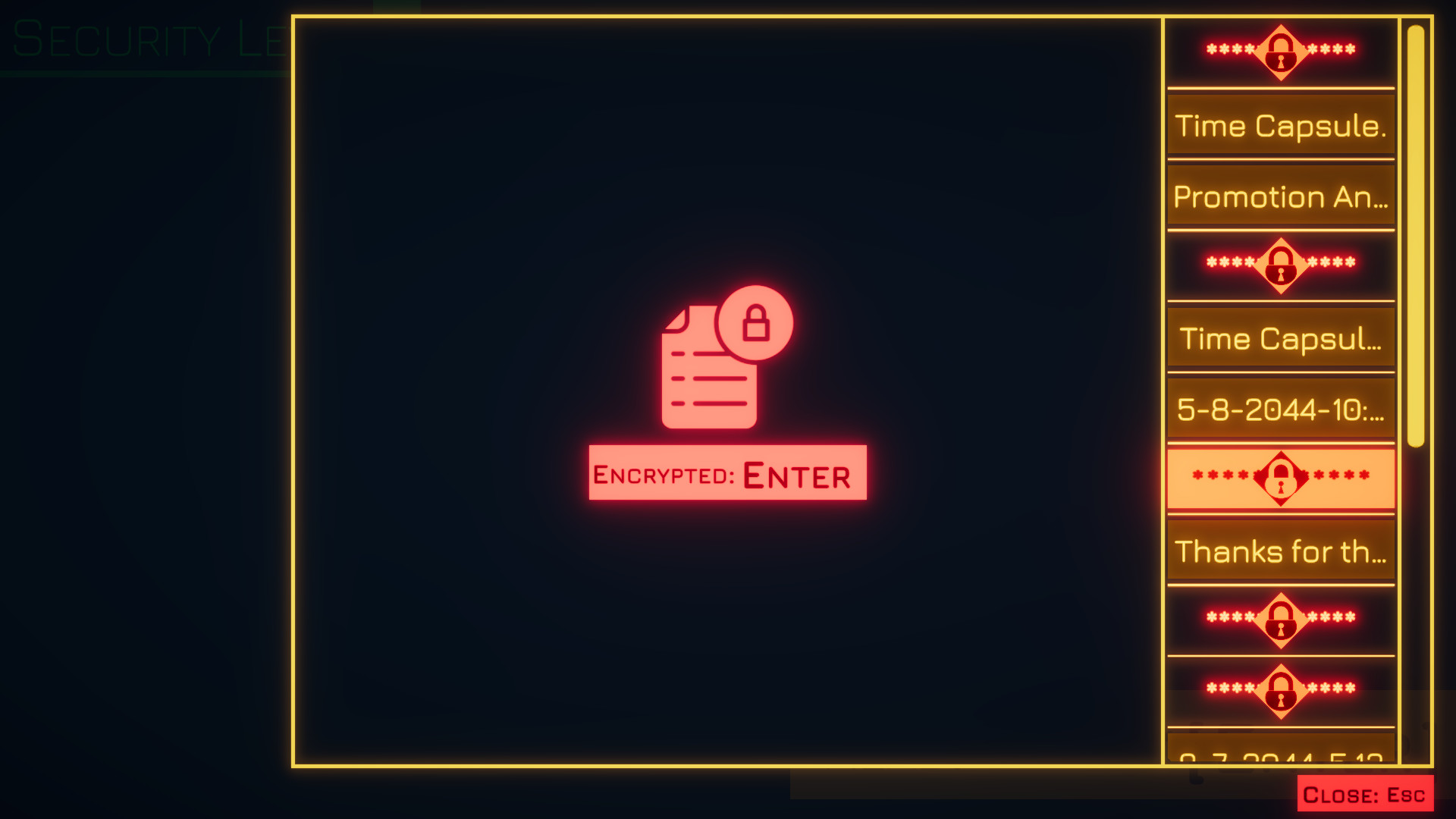

Storywise, I added a BS excuse that the files were encrypted in a way that they required the previous one in the sequence to decrypt them. This meant that the player could only read them in the correct order.

Moreover, since any cutscenes viewed after reading these files would also need to be changed drastically, I instead made it so that the first file would be unlocked right before the last cutscene. This meant that the player could not read any of the encrypted files before that. This drastically cut down on the amount of branching dialogue I had to do.

It was just a convenient excuse to minimize the amount of work I had to do. However, it affected the story in ways I didn’t expect. The player would now get more and more unreadable files after each level. The encrypted files were sprinkled between all levels(starting from the very first). There was no way any player who had bothered with the files would miss them. This meant that the player would eagerly await the moment they’d get to open glowing red files. And it was a treat to see players do that as well.

It was just a convenient excuse to minimize the amount of work I had to do. However, it affected the story in ways I didn’t expect. The player would now get more and more unreadable files after each level. The encrypted files were sprinkled between all levels(starting from the very first). There was no way any player who had bothered with the files would miss them. This meant that the player would eagerly await the moment they’d get to open glowing red files. And it was a treat to see players do that as well.

Takeaway: Give the player something they can’t use and they will eagerly anticipate the day they finally get to use it.

If you think about it, having the files ordered like this is convenient to the point of being a plot hole. So instead, I turned that into a plot point.

The AI wants to test you. They want to know whether you are just a hacker who wants to drown in the thrill of solving puzzles or someone who yearns to know the truth of what happened. And so, the AI intentionally placed the files in such a convenient way because there was no way an inquisitive hacker with a conscience would leave it alone.

Takeaway: Make your story flaws/conceits part of the story.

The encrypted files were distributed in such a way the last few files were obtained in the first batch of levels. It sort of emulated how you were getting to the root of the mystery.

Additionally, major parts of one character’s arc happened to be contained in those late-game files. This meant that that character’s first impression ended up being rather different than what she ended up as. This made the final reveal that much more potent.

And this all just a coincidence due to one lazy decision I made.

Takeaway: Sometimes even the smallest of decisions can influence the story.

The final choice:

The final ending is ultimately determined by a binary choice: To let the AI survive or to terminate it.

Kind of a letdown after all the BS I spouted in this blog. However, I think it’s still appropriate.

No matter what the player character’s actual motivation is, I felt that both choices were possible for his character at the end of the game. So I kept both and let the player decide for themselves.

Takeaway: The presence of any choice implies something. Each choice represents alternate motivations or maybe multiple simultaneously possible motivations.

Additionally, the game makes it so that the choice most story-skippers will pick(the first one) contains the least amount of dialogue. So the players that want to focus on the puzzles will get what they want.

Unfortunately, I don’t think I managed to utilize this properly. This is the only choice in the game(aside from the final choice) and there probably were many more opportunities to add choices.

The game also shortens its dialogue sections for story-skippers. Again, this was also not utilized to its full extent as not all cutscenes do this.

A recent game, Katana Zero, managed to perfect this to an art. I wish I had played it before making Control:Override. The conversation system there would have been perfect for a rude, self-confident hacker.

Takeaway: Acknowledge that no matter how much effort you put into the story, there will always be players who skip it.

With this approach I was able to keep the rather text-heavy story manageable and optional for the player.

Embracing Restrictions:

One more thing I heavily leaned on while designing the story was to embrace every limitation I had and integrating it in the story.

For example, I knew that most of the story exposition would be on past events that take place in the non-cyber world. The abstract art style would not make sense there. I could not animate cutscenes with a detailed artstyle with my skills. I didn’t have the budget to hire anyone for that either. The remaining choice was to have audio logs. And I didn’t have any budget for VA.

Then I realized that I could just have text transcripts for them. Then I made opening those files work exactly like an audio recording(complete with a play button) except without any audio because it was amusing.

And then I also realized that I could make these recordings part of the story in the form of a surveillance plot.

There are other examples such as the game acknowledging that the encryption thing was stupid and was meant to make the player curious. And since the dialogue in question plays after reading those encrypted files, the player will most likely agree.

The game’s story scenario is contrived. But these restrictions often resulted in more and more ideas to integrate into the story. I simply do not think the Control:Override’s story would have turned out the way I did if I did not have so many budget restrictions.

Takeaway: Embrace your restrictions. Make 4th wall breaking jokes out of them if possible.

I think you can start to see why I said designing instead of writing. I did not sit down and write the entirety of the story in one go. All of these story elements are the result of gradual restrictions I kept placing on the characters and the story. I did not plan much at first.

I have several story drafts for yet to be made games sitting around in a folder in my computer. Yet this game, despite not having a story in the first place, ended up with a surprisingly intricate story. And much better than any of my drafts. In fact, I’m rather amazed how well most things came together at the end.

I’m not trying to say that a game‘s story can’t be planned early. Just that I haven’t been able to so far. But I have learned one lesson:

Takeaway: Don’t stress too much about coming up with a detailed story if you’re having trouble. Just let the game grow and build a story around that.

Collaborating on the story

While I wrote the majority of the story on my own, I asked my composer to be the editor.

I wrote the basic draft for conversations/text logs on google docs and he highlighted possible issues via google doc comments.

The script went through several revisions throughout the development period. I’d say that while the skeleton of the story(even the ending) were the same, the actual events of the story changed a lot. And in all cases, the next iteration of the story was better.

I often get tunnel vision with story elements and I can’t envision the story without them. At times like that, simply having another voice of reason helps. Just hearing another perspective is often enough.

Anything I regret?

If there is one thing I’m unsatisfied with, it’s the epilogue for the default ending(the “bad” ending if you will) I had to remove after some discussion with my editor. This ending confronts the player for ignoring the story to just play the puzzles in a rather 4th wall breaking way. It makes it rather obvious that there is more to the story but it does not convince the player that said story is worthwhile.

In various games such as 999, bad ends were used to surprise the player while delivering some extra information that helped the player figure out the larger story. Said epilogue was also written for this purpose, I was not fully satisfied with how it turned out and we were unsure if a story skipping player would want to go through several pages of text(again, no budget for cutscenes). So, it was cut. I still think that the game would be better if I kept it. But hey, what’s done is done.

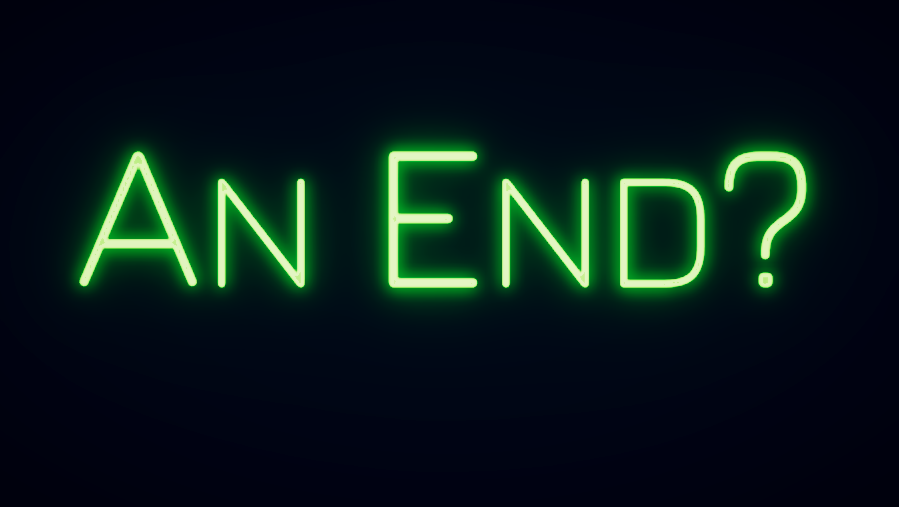

At the time of writing, Most people seem to have gotten the “bad” ending(the first one). Most players seem to not have bothered with getting the good endings. However, I had mistakenly turned off credits in the release build and didn’t notice for two weeks(ouch!), This matters because the credit was followed by this:

Fun fact: None of the endings ever say “The End”.

“Are you really satisfied with this ending? Are you sure that there isn’t more to the game?”- I wanted to evoke this question in the minds of every player who reached the “bad” ending. I do not know how effective this actually ended up being as most of the players did not see this.

And without that, I suppose most players just turned off the game after the ending. Most of the player activity was before that and probably affected the ending achievement%.

Another thing I’m not entirely satisfied with is the lack of relation between gameplay and story. As I said, the story was designed to not interfere with the gameplay. You could just rip out the puzzles and replace it with some other form of gameplay vaguely related to hacking. What I have doesn’t cause ludonarrative dissonance but at the same time it also fails to achieve ludonarrative resonance(or ludonarrative harmony or whatever you want to call it).

I’d also say that I wasn’t able to make use of the biased protagonist/unreliable narrator as much as I should have. I would like to tackle a similar game in the future. An entire game devoted to the idea of deceiving the player sounds interesting to me.

Still, I’d say(from player reception to the story) that the story ended up being much better than I expected. However, being so heavily involved in this game’s story made me understand that I probably should not be responsible for writing the entirety of the story for future games. For the lack of a better word, I’m… inconsistent in terms of writing output. I had mentioned in my previous post that the release of the game was delayed due to the story. I had finished all of the 47 levels in the game by the end of December 2020. The game was released on April 20 (After a one month internal delay). These 4 months were spent mostly on wrapping up the story.

For me, creativity comes in short, unpredictable bursts. Even if I force myself to write for hours, I’ll typically only be productive for the first few of them. Sooner or later, I get stuck on a line. And no amount of sitting in front of the computer helps with that.

Switching tasks helps. Like fixing a bug or writing a different part of the story. Then, at 1AM on a sleepless night or during literally anything except work, I’d get a flash of inspiration and knew exactly how to continue from the point I got stuck. This was fine in the early phases as I was under no deadline and always had something else to do when I got stuck with the story.

However, once I was done with all the levels, the story became the bottleneck. I’d get stuck on a line and not make any progress for days. And I couldn’t just move on to a different part of the story since most of it was done. I also had classes and exams during this period. There was also the time when we had to start preparing for release(playtests, contacting youtubers, new trailers etc etc). It was hard to just focus on the game.

It got so bad that I had to delay the release from March to April just because of the story.

My loose approach with the story had kept things flexible at the start but made things hell afterwards.

That said, I’m happy with how the story turned out. I don’t think it is possible for me to work on a game and not get involved in the story. But perhaps I should leave the actual writing to someone else. I can’t write on a deadline to save my life.

What’s next?

In my next post, I’ll talk about the design of Control:Override’s puzzles and mechanics.